The reason why one of India’s biggest blockbuster films, Sholay, still resonates with Indian audiences across generations is because it is structured around the navarasa tradition of Indian aesthetics, which encompasses all the nine emotions, according to screenwriter Anjum Rajabali.

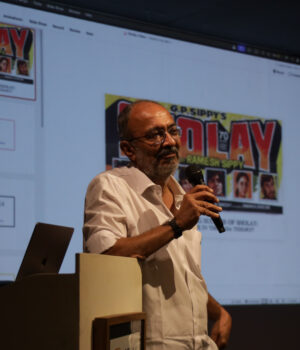

Speaking at the Museum of Goa in Pilerne, during a recent ‘MOG Sunday’ session which celebrated Sholay completing 50 years, screenwriter and cinema theorist Anjum Rajabali said the film’s mass appeal cannot be explained only through its popular stars, slick action or dramatic dialogue. Instead, Rajabali underscored the film’s “emotional design,” structured around the navarasa tradition of Indian aesthetics.

The MOG session explored how the 1975 film directed by Ramesh Sippy reflects the nine rasas or emotional essences, namely shringara (love/beauty), hasya (laughter), karuna (sorrow) raudra (anger), veera (heroism/courage), bhayanaka (terror/fear), bibhatsa (disgust), adbhuta (surprise/wonder) and shanta (peace/tranquility). The foundational navarasas were outlined by sage Bharata in the Natyashastra, an ancient cultural treatise.

When asked which other films comprehensively exploited the navarasa tradition of performance, Rajabali said: “I think Amar Akbar Anthony perhaps would have many of them. Mughal-e-Azam had many of the rasas too. but it did not have, for example, comedy,” the screenwriter said.

He said rasa is not an intellectual layer added to cinema but something the viewer experiences instinctively. Explaining why audiences continue to engage with characters even when they know them well by now, Rajabali pointed to the scene involving Jai’s (played by Amitabh Bachchan) ultimate sacrifice on the altar of friendship at the film’s climax.

“Dramatic irony is where the audience knows something that the character doesn’t.” He used this and similar examples to show how emotions such as fear, grief, and loyalty operate beneath the plot of arguably one of India’s biggest blockbuster films of all time.

Rajabali noted that comedy in ‘Sholay’ functions as an emotional counterweight rather than a detour. Situations involving characters like Soorma Bhopali and Basanti in the film allow humour to stem from personality and circumstance.

“People laugh uncontrollably at the weight of the dialogue and the way the situations arrive unexpectedly,” he observed, adding that humour coexists in the movie with danger without diluting the latter.

He also reflected on how the film’s casting shaped rasa. Recalling the choice of Amjad Khan, he said Salim Khan believed the actor could evoke menace without theatrics. “There was no feeling in the eyes at all — dead eyes,” he quoted Khan, the film’s co-writer, as saying, to explain how the character of Gabbar Singh allowed disgust, terror and hatred to build naturally.

On the relevance of rasa theory in cinema today, he said the emotional experience is inseparable from how audiences engage with film. “You don’t have to be familiar with the theory,” he said. “You just feel it.” When asked whether removing even one rasa would weaken a story like ‘Sholay’, he said its appeal would certainly have been reduced.

Rajabali said the endurance of ‘Sholay’ lies in its ability to balance high-stakes drama with layered emotional experiences. While he believes some rasas, such as shanta, remain underused in Indian cinema, he noted that the film still “arrives at a kind of tragic equilibrium” that keeps it emotionally complete and culturally alive.